Gender equality in marathons: from historical exclusion to current recognition

11/04/2025 22:20Access to long-distance running events, like marathons, has long been a male-dominated domain. Organizers and sports institutions were staunchly opposed to female participation, while the media depicted women’s sports as marginal, dangerous, and unsightly. The gradual opening of athletic events to women took several decades, thanks to the relentless efforts of many determined women. The marathon is one example, as it opened up quite late, due to significant acts of resistance.

As the Paris marathon 2025 approaches, statistics show that gender parity is not yet achieved, but it continues to increase. Out of 55,000 participants, 13,750 are women, representing 25% of the registrants. The marathon, one of the premier distances in athletics, has historically been resistant to female participation.

For decades, women were completely excluded from major sporting events. Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympic Games, was firmly against female participation in athletics and major competitions. “The Olympics should be reserved for men, with women primarily tasked with crowning the victors.” (Pierre de Coubertin, “La Pédagogie sportive”, 1912.) “It is indecent for spectators to witness a woman’s body breaking down in front of them. Moreover, regardless of the athlete’s strength, her body is not made to endure certain shocks.” He argued against the inclusion of female athletes, upholding the medical notion of the time that women were too fragile to engage in sports.

In the early 1900s, physical activity was suspected of causing female infertility, transforming them into men, and encouraging promiscuity by exposing their bodies. Pierre de Coubertin and his supporters claimed that women “are not made for sports, for medical, aesthetic, and moral reasons. It disfigures them, strips away their femininity, and poses a danger to their health, society, and especially family life, as it prevents them from properly attending to domestic duties.” (Barbusse, 2016, p121, citing Pierre de Coubertin) Banning women from running was also a way to hinder their emancipation and deprive them of freedom, reflecting a fear of them becoming independent and ultimately equal to men.

Detractors of women’s sports argued that engaging in sports contradicted the presumed fragile constitution of women and was disruptive. The scientific community supported the notion that the impacts from sports activities, like running, might cause the detachment of women’s reproductive organs. This is why the 400 m hurdles only became an Olympic event for women in 1984. Pierre de Coubertin fought against women’s access to competitive sports, asserting that “sport is a symbol of virility.” (De Coubertin, “Essai de psychologie sportive”, Jérôme Million [1913] 1992, p151.)

| Alice Milliat, an advocate for women’s access to competitive running

Alice Milliat, an activist, stood up to the baron multiple times, demanding women’s participation in Olympic athletics. This feminist also led women’s associations like Fémina Sport and Ondine de Paris from 1912, and founded the Federation of French Female Sports Societies, organizing women’s Olympic games. Women’s races were organized, though the distances were far from marathon length.

Sociologist Béatrice Barbusse highlights the organization of the “Marche des midinettes” in 1903, a race from Tuileries to Nanterre with over a thousand participants, and the “Cross de Chaville” near Paris on April 28, 1918, the first race with women competing in shorts and jerseys. (Barbusse, 2016, p122) This first women’s cross-country of 2400 meters left a mark as women showed their legs and arms and competed, which was considered indecent.

The next day, the press was critical but intrigued, as Broucaret illustrates: “The 42 participants dressed like men, in jerseys and shorts, attire deemed indecent by detractors. Still, the event was supported by leading sports journals of the time, L’Auto and l’Echo des Sports.” (Broucaret, 2012, p18) Women’s sports “did not emerge from a gradual opening of male sports clubs to women, where their presence was forbidden, but from the activism of a few pioneers, led by Alice Milliat.” (Broucaret, 2016, p122) Thanks to the efforts of indomitable activists like Alice Milliat, often forgotten, women today have the right to start races alongside their male counterparts.

| A step forward and two steps back

In athletics, women participated for the first time in some events at the Amsterdam Olympics in 1928: the 100m, 800m, 4×100m, high jump, and discus throw. The idea of women running a marathon was unimaginable. Even though Coubertin’s successor as IOC president, Henri de Baillet-Latour, allowed women to compete, “hostility towards women’s sports remained,” notes sociologist Fabienne Broucaret (Broucaret, 2012, p16). This progress was short-lived. During and after the 800m event, won by German Lina Radke, competitors appeared exhausted, some collapsing as they crossed the line. This is what the press and the IOC recalled from opening this event to women, decrying “those poor women.”

The race created an outcry among opponents of women in athletics and the media, who distorted reality to perpetuate beliefs that women’s physiques made them incapable of physical exertion. Lina Radke’s lack of femininity was also criticized. Justifying one’s identity as a woman in the male-dominated sports world was a crucial issue at the time. Today, these debates persist when female athletes are deemed too masculine.

Since the Amsterdam Games’ 800m, women were barred from running distances over 200m at the Olympics until 1960, a span of 32 years. A major event was needed for women to access long distances like the marathon. In Boston, USA, a 20-year-old woman managed to enroll in the city’s marathon thanks to her coach, who registered her only as K. Switzer, for Katherine Switzer.

| Katherine Switzer, courage and symbolism

On April 19, 1967, Katherine Switzer lined up, made up for the occasion (perhaps to assert her femininity in a men’s event?), accompanied by her coach Arnie Briggs and her hammer-thrower boyfriend, Tom Miller. The group stayed together to avoid suspicion.

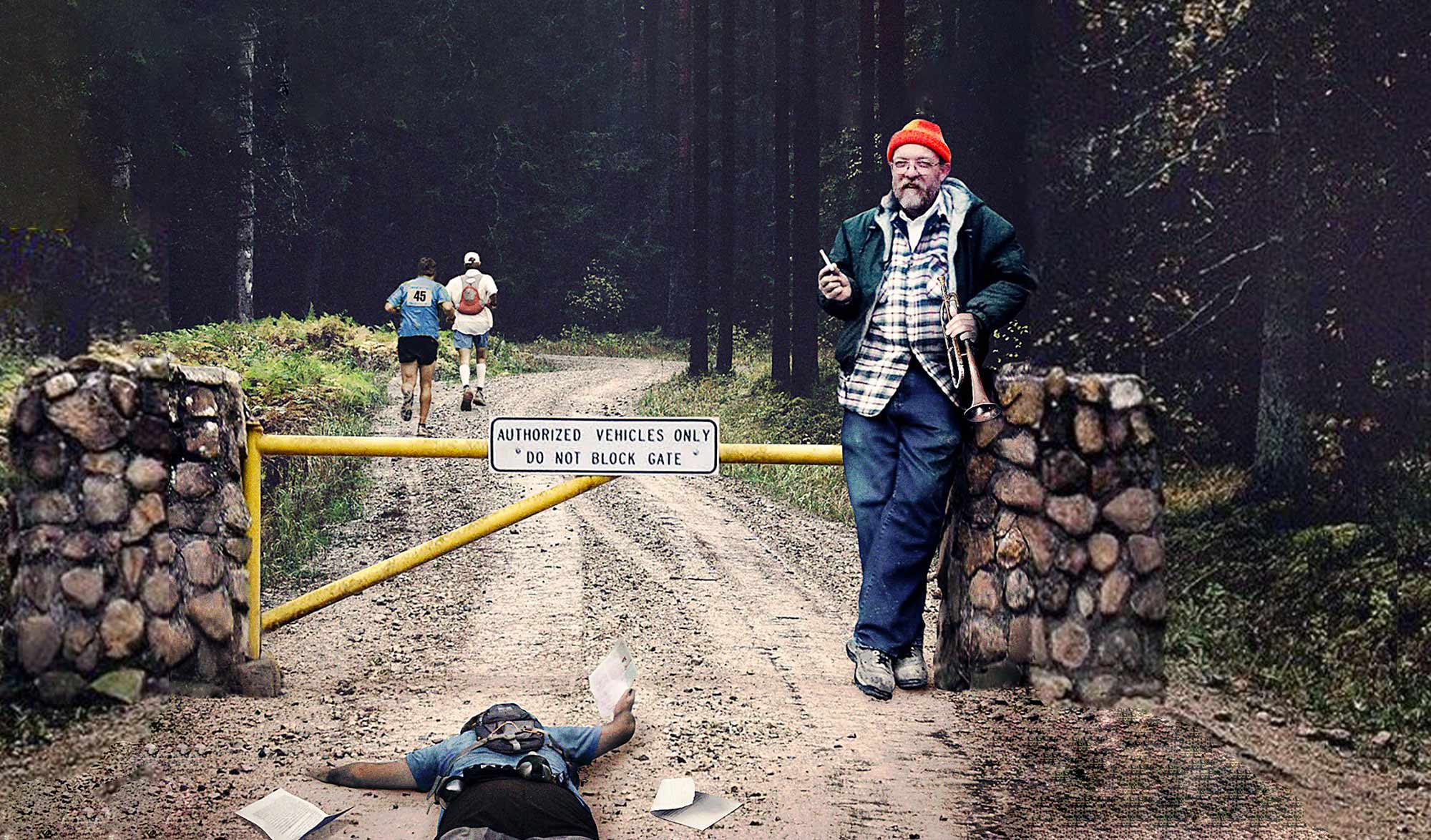

After only six kilometers, an organizer rushed at Switzer, shouting “Get out of my race and give me those numbers!” Photographers captured this moment. The coach pushed the organizer away, and the young woman kept running, finishing the marathon in 4h20. Switzer persisted, wanting to prove women could run 42.195 km. The next day, the press focused on her clandestine participation and the confrontation with the organizer. However, she was disqualified from the race and suspended by the American Athletic Federation. The media dubbed her “the girl who defied marathon organizers” (Patrick Karam and Magali Lacroze, “Le livre noir du sport,” 2020, p53). These now-iconic photos were widely circulated and remain impactful today.

“The powerful image and embodiment of a struggle led to general awareness and the gradual integration of women into competitive sports. Katherine Switzer would win the women’s marathon in New York seven years later!” (Patrick Karam and Magali Lacroze, 2020, p54) Switzer’s bravery led to a broader acceptance of women’s participation in competitions. As Béatrice Barbusse explains, women “won their right to run long distances, particularly marathons, outside the organized federation movement, which stubbornly refused them, sometimes violently, as shown by a now-famous photo” (Barbusse, 2016, p291).

Switzer’s demonstration of women’s capability led to the Boston marathon opening to women in 1972. Now, 45% of Boston marathon entrants are women. The champion later organized women-only races and participated in 39 marathons, winning the New York marathon in 1974.

Switzer was thus the first woman to officially run a marathon with a bib. The year before, the first woman to unofficially run a marathon without a bib was American Bobbi Gibb (3h21’40). After being refused an entry, she hid in the bushes and joined the race. Fellow runners promised to protect her if she was excluded since running in public spaces was allowed.

| Persistent resistance through the 70s and 80s

In France, during the 1970s, Raymonde Cornou was one of the first women to run a marathon, even when road races were not open to women. She explained in an interview with online journal ABLOCK!: “These races were organized by men, for men, and we couldn’t even register. It took until the mid-70s to access them more easily.” (Raymonde Cornou, interviewed by Sophie Danger for ABLOCK!, 2022)

Raymonde Cornou repeatedly defied bans to accompany her runner husband. “I pretended to participate with a bib, though I didn’t have one.” (Raymonde Cornou, interviewed by Sophie Danger for ABLOCK!, 2022) She even ran in a men’s French marathon championship. The French Athletics Federation representatives were not pleased with this covert participation. She detailed: “They came after me in a car and tried to push me into a ditch. I struck the car, and we exchanged some harsh words. They told me I had no right to run.”

Raymonde Cornou stood her ground, arguing she was accompanying her husband. Organizers then disqualified him, mistakenly disqualifying another runner instead. Raymonde Cornou was then banned for life by the FFA, to which she responded she didn’t care since she wasn’t licensed. She persisted at another French marathon championship, and this time, organizers realized stopping Raymonde Cornou was futile. Thus, she became the only woman to participate, even without a bib. Other races were against her participation, despite her threats to alert the press or run with a placard highlighting officials’ refusal to let her run. “They eventually had to let me participate,” she summarized, referring to the indomitable athlete.

Raymonde Cornou defied bans, managing to run alongside men despite widespread scorn. She was ignored at the finish, excluded from podiums and rewards, and faced jostling and criticism from fellow runners. In response, she boasted of picking bouquets from field edges during races to cross the line with them, celebrating her run. “I faced runners’ sarcasm. Some pushed me, said I didn’t belong, that I should be at home. I heard a man in the crowd make a derogatory comment about my chest. I stopped, went back, slapped him, and continued the race. A journalist reported this incident, and it still follows me today!” (Ibid)

Resistance from organizers and runners was fierce, even violent. Ideas of women’s place being at home and merely being pretty and obedient were prevalent, hindering women’s access to running. However, Raymonde Cornou participated in almost every race, traveling Europe and the world to run marathons. She became popular, inspiring many women, participating in numerous races, and garnering increasing support at events.

| A slow but progressive opening for marathon women

In 1972, the Boston marathon opened to women, followed by Berlin in 1974, then Madrid in 1978, and Stockholm and Paris in 1979. In 1982, women could participate in the European marathon championships, the following year in the World Championships, and in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. American Joan Benoit took gold in 2h24’52. But it wasn’t the Olympic champion who grabbed media attention in 1984. Swiss Gabriela Andersen-Schiess, entering the stadium 20 minutes after the winner, astonished the public. The marathoner staggered, almost stopping until someone in the crowd encouraged her, then the entire stadium joined in. That day, she finished 37th in 2h48’42.

Encouraged by the initially shocked, then admiring, crowd, this event marked a progressive mindset shift regarding the tenacity and place of female athletes in an event long reserved for men. While 1928 Olympic 800m Lina Radke’s win shocked public opinion, the 1984 Olympics finally reflected admiration for women running at the highest level.

The intense battles led by pioneering, determined women like Switzer, Gibbs, Cornou, and Milliat have allowed today’s women the right to compete on equal terms with men in long-distance events like marathons.